A Case Of Environmental Injustice: Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository

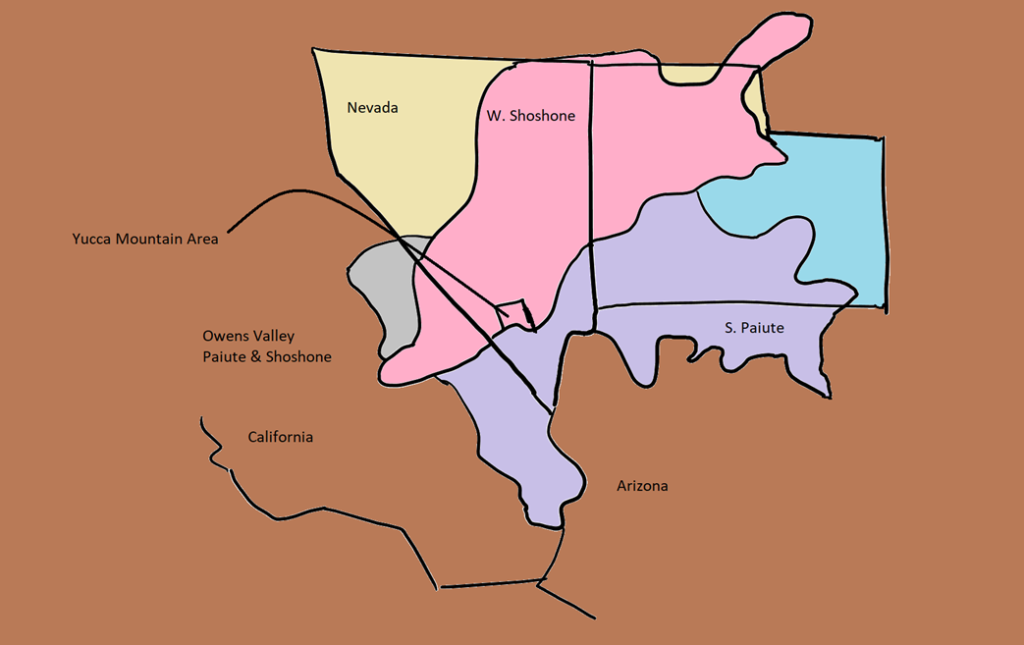

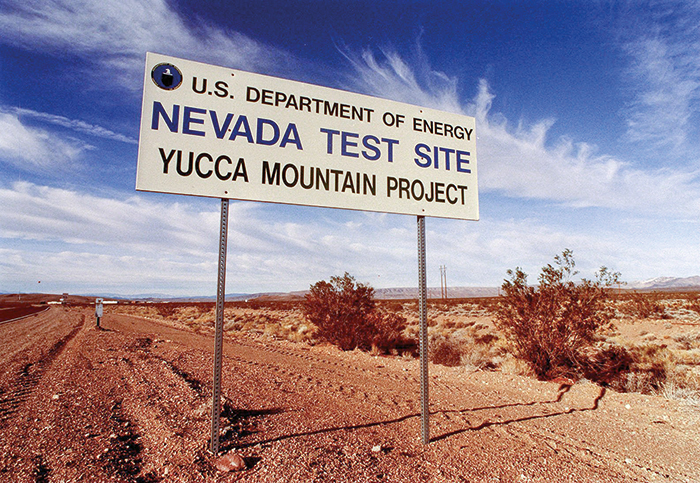

Yucca Mountain Ranges (U.S. Department of Energy)

Introductions

In 1987, the Nuclear Waste Policy Act Amendments (NWPAA) assigned Yucca Mountain, adjacent to the Nevada Test Site, as the permanent storage site for nuclear waste in the United States (Tamayo et al. 2020). The radioactive waste was stored by burying radioactive waste deep into the ground after it was completely sealed in a dry cask (Kyne and Bolin 2016).

The federal government owns approximately 85% of the lands situated in Nevada (Tamayo et al. 2020). Two areas that are highly contaminated by radioactive waste are located on American Indian-owned land. One of them is the Yucca Mountains. Two Native American tribes live close to this site among other marginalized groups: Paiute and Shoshone tribes.

This creates a problem because they do not have the financial and political capabilities to prevent this site from being permanent storage for nuclear waste (Tamayo et al. 2020). In addition to the health impacts from exposure to radioactive waste. The Native American tribes voiced out that Yucca Mountain is much more than a national sacrifice zone that the Federal government labeled, an area that holds no purpose besides storage of nuclear wastes. To the Paiutes and Shoshone tribes, Yucca Mountain gives them a sense of place to continue to have deep connections to their cultural past – a sacred land (Endres 2012).

Despite opposition from the Paiutes and Shoshone tribes, Yucca Mountain was still assigned as radioactive waste storage. During one of their attempts to communicate with the government, they were told, “We are not interested in buffalo stories” (Tamayo et al. 2020). This is a case of environmental injustice because even though they have the highest risk of exposure, they could not participate in the decision-making process. Simply because they do not have the financial or political capabilities to participate. The federal government stated that it was for the benefit of the great majority.

In an attempt to replace the previous model used for deciding where to store nuclear waste, known as Decide-Announce-Defend (DAD), that practices environmental injustice. The First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit stated that “environmental justice demands the right to participate as equal partners at every level of decision-making, including needs assessment, planning, implementation, enforcement, and evaluation.” Currently, it appears that there are still no permanent storage sites for radioactive waste after the operation at Yucca Mountain has been stopped.

Containment Chemistry and History, Source of Contamination

As previously mentioned, the Yucca Mountains have had a long history with radioactive waste and the presence of nuclear radiation. During the early to mid-1950s, the Nevada desert was subjected to copious amounts of radioactive weapons testing. Most notably, the infamous atomic bomb (Willett et al. 2020).

A-Bomb Test, Yucca Flat, Nevada 05/01/1952 (Fletcher 2011)

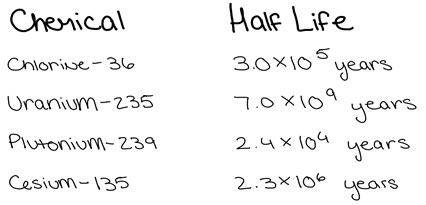

After testing was completed, the flats remained a favorite testing space for the U.S. Military for 20 more years. Over 800 atomic and underground nuclear weapons tests took place in the 200 square miles of Yucca Valley. (Willett et al. 2020) Here, the nuclear byproducts sit in the sand and soil as radioactive isotopes of chlorine-36, uranium-235, plutonium-239, or cesium-135. Making their way into the water table and sticking around for centuries due to their long half-lives. (DOE 2009) After the military abandoned the area, many “downwinders” fell victim to the tests’ radioactive fallout. On account of the already present nature of radioactive waste, the Yucca mountains were proposed as a potential site for waste storage by the NWPPA. (DOE 2009) Researchers estimated that a storage facility would have to be designed to hold over 70,000 metric tons of radioactive waste.

Half-lives of radioactive contaminants

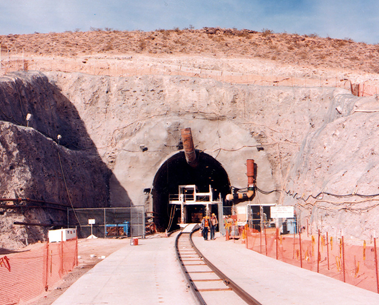

During the proposal period for the storage site in the early 1990s, researchers sought to determine the safety of the groundwater surrounding the facility. High levels of radioactive isotopes such as chlorine-36 were found. (Kleist 2020) Having sept through the highly porous rock layers into the groundwater and the areas proposed for tunneling. Despite the widespread protest from the local native population and ecologists alike, construction of these massive waste tunnels continued. It was only in 2010 under the administration of former President Obama that the development of over 60 miles of storage tunnels stopped. (Endres 2012)

The entrance of the 60-mile tunnels in the Yucca Valley, these massive tunnels are currently left uninhabited (Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2007)

Intersection With Environmental Justice

The nuclear waste contamination at Yucca Mountain is affecting Native communities, specifically the Shoshone and Paiute communities (Western Shoshone, 2017). As mentioned earlier, the Yucca mountain is a national sacrifice zone, and it is not just any piece of land; it is deeply rooted in the Shoshone and Paiute communities’ history (Corbin, 2004). Historically and spatially uneven politics of pollution intersect with personal and geographical imaginations. And refusing to acknowledge Aboriginal title and American Indian objections to high-level radioactive waste disposal, the US government, violates its laws. This occurs due to a confluence of historical, social, and political factors (Houston, 2012).

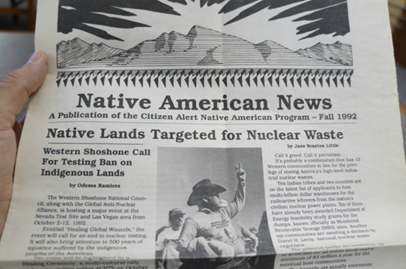

A copy of Native American News from 1992 detailing the fight against the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Site (Broze 2019)

Western populations see these places like the wilderness and do not understand the attachment or care the native communities have with the land. As a result, they pollute and contaminate the land causing the Native communities and, in this case, the Shoshone and Paiute communities to get affected by these nuclear wastes. Places that are marked by environmental injustice are often referred to as “sacrifice zones”—areas that bear an unequal environmental burden for the greater “public good” of economic and national development (Houston, 2012).

Proposed Solutions

The capacity of nuclear waste in Yucca Mountain should not exceed its limits. Existing nuclear waste should be controlled/treated with caution to avoid creating more danger and control creating new nuclear waste.

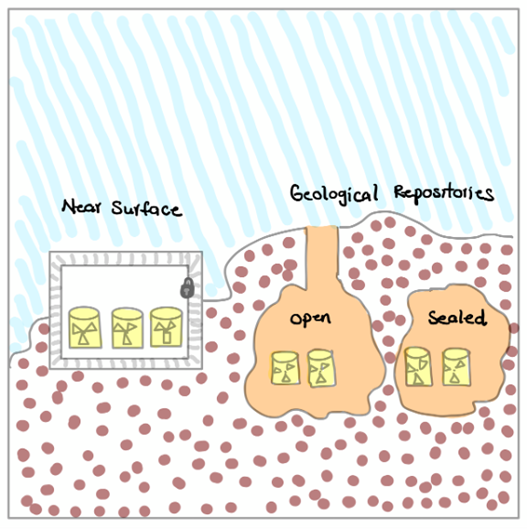

Nuclear waste should be disposed of properly depending on its content: near-surface should be adequately locked, while geological repositories should be open (contact with the environment) or sealed (underground) (Tamayo et al. 2020).

The solution to the problem of nuclear waste remains as first proposed by the National Academy of Sciences in 1957: mined geologic repositories that isolate the waste from humans and the environment. (MacFarlane, et al. 2006) The development of disposal facilities that provide long-term isolation through the use of passive engineered and natural barriers rather than through the continued human control and maintenance. The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) standard of 1985 set containment requirements limiting releases of radioactive species for ten thousand years, individual protection requirements limiting annual exposure (doses) for one thousand years, and groundwater protection requirements limiting radioactivity in groundwater for one thousand years (MacFarlane, et al. 2006). EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) and NRC (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) regulated the controlled area extended no more than five or ten kilometers from the primary site of waste emplacement. Later, the five to ten-kilometer boundary was enlarged to eighteen kilometers. The critical group at risk would be likely to live near Yucca Mountain and be exposed to radiation through contaminated groundwater. (MacFarlane, et al. 2006)

Takeaways

Environmental Justice (De Vries 2017).

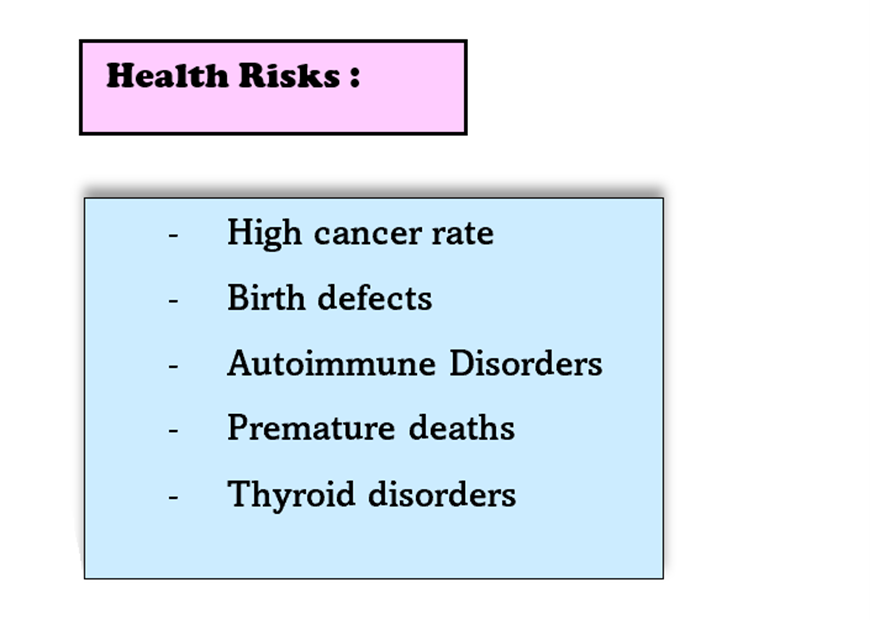

With the long history of underrepresentation of indigenous communities, it is no surprise that the Yucca Mountain waste facility is still a possible, disposable site despite the long list of hazards associated with it. The Paiute and Shoshone tribes have been subjected to radiation contamination for decades. They are developing cancer, asthma, and reproductive problems (Houston 2012). Unfortunately, it is not as easy to educate and prevent the continuation of radioactive pollution as you can with other contaminants. Therefore this complex problem needs an even more complex solution. To help the public understand the risks associated with this contamination, the EPA should present a yearly analysis of the contaminants present in the soil around the sites and develop natural barriers to help slow the leaching of radioactive isotopes into groundwater. It should be the responsibility of the US government to help set the remedial efforts into motion as the radioactive weapons abused throughout the area were the primary source of contamination. Most importantly, however, the voices of the local communities, especially the Paiute and Shoshone tribes, must be amplified dramatically. Without the voices of these communities, they will continue to suffer in even the most basic ways.

References

Broze D. Trump is Trying to Revive the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Site | Intercontinental Cry. [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. https://intercontinentalcry.org/trump-is-trying-to-revive-the-yucca-mountain-nuclear-waste-site/.

Corbin A. Yucca Mountain – United States. Sacred Land. [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. https://sacredland.org/yucca-mountain-united-states/.

Endres D. 2012. Sacred Land or National Sacrifice Zone: The Role of Values in the Yucca Mountain Participation Process. Environmental Communication. 6(3):328–345. doi:10.1080/17524032.2012.688060.

Houston D. 2013. Environmental Justice Storytelling: Angels and Isotopes at Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Antipode. 45(2):417–435. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01006.x.

Kleist T. Yucca Mountain: Faster Water Flow Undermines Project Safety, UNR Geologist Says. [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. https://www.kunr.org/post/yucca-mountain-faster-water-flow-undermines-project-safety-unr-geologist-says.

Kyne D, Bolin B. 2016. Emerging Environmental Justice Issues in Nuclear Power and Radioactive Contamination. International journal of environmental research and public health. 13(7). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13070700. [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. http://www.proquest.com/docview/1805484759?pq-origsite=primo.

MacFarlane A, Ewing R, Ewing RC. 2006. Uncertainty Underground: Yucca Mountain and the Nation’s High-Level Nuclear Waste. Cambridge, UNITED STATES: MIT Press. [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/washington/detail.action?docID=3338498.

Neisius M. Western Shoshone Nation Opposes Yucca Mountain Nuclear Repository – Commodities, Conflict, and Cooperation. [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. https://sites.evergreen.edu/ccc/warnuclear/shoshone-tribe-opposes-yucca-mountain-nuclear-repository/.

Schneidmiller C. 2017. Early 2018 House Vote Expected on Yucca Mountain Bill. ExchangeMonitor. [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. https://www.exchangemonitor.com/early-2018-house-vote-expected-yucca-mountain-bill/.

U.S. Department of Energy Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management. 2008 Jun. Yucca Mountain Repository License Application: Safety Analysis Report. :100.

Willett J, Tamayo A, Kern J. 2020. Understandings of environmental injustice and sustainability in marginalized communities: A qualitative inquiry in Nevada. International Journal of Social Welfare. 29(4):335–345. doi:10.1111/ijsw.12456.

Provide Feedback